24-hour party people: raving and rebelling in Manchester’s Hulme Crescents

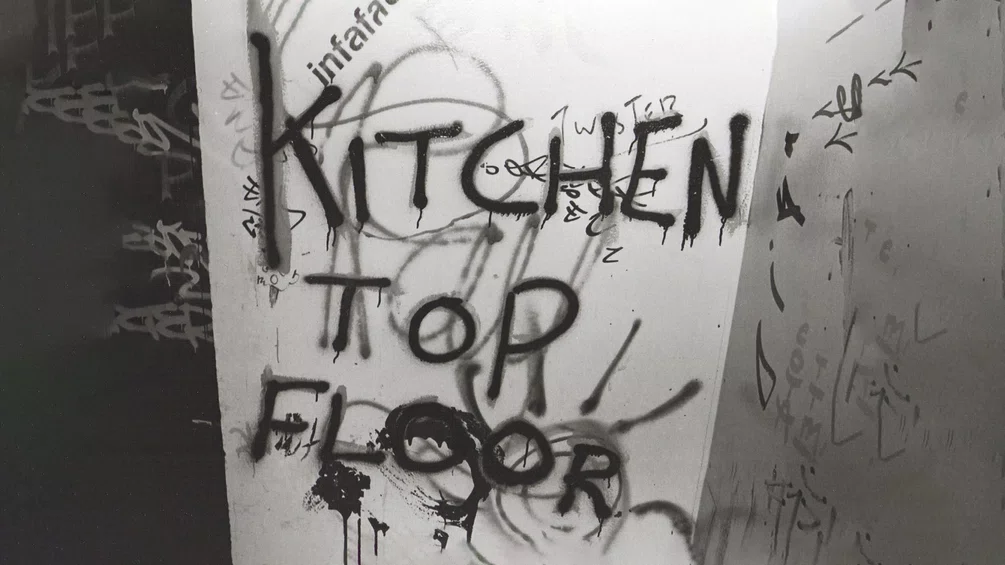

Welcome to Hulme Crescents, Manchester, an inner-city public housing experiment that, in the ’80s, became an amphitheatre of chaos and creativity. In this estate, acid house ravers, New Age travellers, punks, b-boys and Rastafarians converged, striding up dark stairwells, through a maze of graffiti-covered walkways, toward the thumping bass emanating from The Kitchen, a 24-hour shrine to music. “It was an all-night gaff,” remembers Happy Mondays’ Shaun Ryder, who first visited in 1986. “I wasn’t thinking, ‘This is DIY music culture’. It was a fucking mega gaff, somewhere where we were off our fucking faces until 7 in the morning when the cops showed up.”

Despite Ryder’s nonchalance, this historic development — the largest of its kind in Europe, where vast lawns were encircled by four run-down, half-moon-shaped buildings — and its round-the-clock parties are now being reappraised by those who remember living, dancing, and rebelling against the status quo there. Three decades since its demolition, they now believe it had a significant impact not just on their own lives, but on the cultural force of the city itself.

Al Baker, a photographer and former resident, remembers this grungy autonomous zone, where squatters, students and a star-studded cast of musicians would mingle, as representing a “new way to live”. Revellers were “dancing in the ruins” of society under Margaret Thatcher’s grim rule, he says, with the walls literally crumbling around them. Later this year, he will publish a new collection of photos from this era, giving an inside look at life in these four blocks — each named after a famous architect: Charles Barry, William Kent, John Nash, and Robert Adam.

Baker isn’t alone in his desire to share this lore. The Kitchen recently appeared in writer Ed Gillett’s encyclopaedia of British nightlife, Party Lines: Dance Music and the Making of Modern Britain. Photographer Richard Davis’ book, Hulme (Manchester), published in December, includes images that he captured while living there, developed in the darkroom he set up in his flat. These photos were recently exhibited in Manchester and Sheffield.

In January, Netflix released Daniel Kaluuya’s claustrophobic dystopian directorial debut, also called The Kitchen. The film has many parallels to Hulme’s anarchic community that feel impossible to ignore. Residents of the gloomy fictitious estate are constantly besieged, yet a thriving culture of resistance — plus a club where the defiant community lets off steam — thrives. These stories remind us that rhapsody can always be found in working class communities where people refuse to let adversity define them.